Yes folks, you are reading post number 300 on BeKindRewrite! Applause! Music! Fanfare! And in monument to this momentous moment, I present the top ten most viewed posts (so far). Click through and read ’em if you haven’t already.

Category: Writing tips

5 Ways to Build a Detailed World Without Boring Your Readers

It’s the year 2053. Earth has made first contact with an extraterrestrial race; socialist aliens who reproduce asexually. You, now a literary giant, are tasked with adapting a sample of Earth literature for the aliens to enjoy. The book is Pride and Prejudice.

You open your well-worn copy to that famous first sentence, It is a truth universally acknowledged that a single man in possession of a large fortune must be in want of a wife…and you break down in tears, realizing this tale of class and marriage will mean absolutely nothing to your audience.

Universal truth, your foot!

Yet this is the challenge science fiction and fantasy writers face every day.

We create whole new worlds to house our stories, then find ourselves struggling to keep up the pace while stopping the action every few paragraphs for a history lesson.

But we don’t have to! With a few tricks of Show, Don’t Tell, we can show our readers a lot about our world without slipping into exposition. The close-up details of our heroes’ personal lives can reveal the big picture of the world they live in.

Like so:

1. Your protagonist’s job

…and the jobs of the people he knows say a lot about your world. If they’re all farmers, your readers see an agrarian community. Make him a moisture farmer in a desert, shopping for robots, and he’s Luke Skywalker. Or make him a starship repairman or a dragon breeder. Whatever the occupation, in one conversation with buddies at the pub about how hard work has been this week and what the government is up to, you can cover:

- The major industries of your world

- Who controls them / has the power

- The biggest problems with society

More useful tools along these lines:

- Living quarters (cave, tent, cryotube, barracks, fortress?)

- School/studies (from a blacksmith’s apprenticeship to a mind control science project)

- News reports (from the town crier announcing the war to a psychic message about falling nanobot stock prices)

2. Your protagonist’s relationships

How was he raised? Does he live with the wife and kids? The wives and kid? Seven generations of his family? Coworkers, classmates, cellmates, refugees? No one at all? This all reveals:

- The society in your world

- The structure of the family

- Barriers between the classes

3. Your protagonist’s traditions

Does he pray before he eats? Does he have to slay a beast to be acknowledged a man? When he attends a funeral, is he watching a body buried, burned, scattered, eaten, or recycled? Do they even have funerals? This reveals:

- Religion – who they worship, where they came from, where they go when they die

- History – holidays can be used to reenact important points in history

Traditions can include:

- Daily rituals: getting up, going to sleep, eating

- Life events: birth, coming-of-age, marriage, parenthood, funerals

- Holidays: festivals and fasts

*Pro tip: A liturgy, specifically words sung or recited at any of these events, can be an especially handy way to sneak in detail.

4. Your protagonist’s speech

Language, slang, shop talk, and industry buzzwords are all great tools to both plant clues and add personality to your world. For instance, your can make up your own:

- Terms of endearment or insult (honey, jerk)

- Titles (husband, wife, king, priest)

- Curse words (…)

- Greetings (hello, hi, good day, hey y’all, yo)

5. Use the appendices, Luke!

Your readers will usually be able to interpret casual references to foreign concepts by the context. But to include more detail, you can always add appendices at the back of the book. Tolkien and Herbert, renowned for their world-building in Lord of the Rings and Dune, both did it. Use footnotes to lead readers to things like:

- Glossary of terms

- Translations of foreign words

- Maps

- Summary of religion and history

What are some of your ideas for showing your world to readers? Tell me in the comments!

—

Thanks to Sky for suggesting this topic! If you have a writing question you want answered, leave it in the Suggestion Box!

Great show-don’t-tell world-building tips for sci-fi/fantasy writers.

How to Sneak in Scenic Description

Setting is as necessary as plot and character, but only as far as it influences plot and character, the way the water-starved planet Arrakis affects everything that happens in Dune.

No one reads a book for the scenery; it’s a nice bonus if described artfully, but it’s not what makes us crack the pages.

Yet so many writers spend paragraphs painting a picture before even touching on the action. Many try a “zoom in” approach, first describing a wide shot, like a city, then zooming in on a particular street or building, then zooming in further to describe a character. Only after all that do they finally get around to the story.

At best, this approach is risky, especially on the first page, when you only have seconds to secure a reader’s attention. So instead of dedicating whole paragraphs to weather, scenery, and character appearance, try dispersing it throughout the action and dialogue.

As an experiment, I’ve written two different versions of the beginning of a story. See which one grabs your attention sooner. Maybe you’ll disagree with me. Let me know in the comments.

VERSION ONE

The city went on forever, a steel and glass jungle clogged with concrete and grime. Skyscrapers rubbed shoulders with factories; trains shoved aside shops and cafés, and crowds oozed through bottleneck alleys.

In the bustle at the station on the corner of 3rd and Main stood a man with a brown coat and hat; a static chocolate freckle in a surging confetti sea. His face was round and crinkled; his eyebrows spikey and gray. He had two fingers shoved in the little pocket where he kept his watch, feeling the tick tock in his fingertips like the pulse in his veins.

It seemed like it was slowing.

How many ticks did he have left before the train came? How many tocks before he stepped aboard for the last time? How many heartbeats before he flinched at the hiss of the air brakes, anticipating the final exhalation of his own rattling lungs?

And then suddenly it was before him, light strobing off its speeding windows, the tracks screeching with sparks. Slower and slower until it stopped, staring at him.

The train was on time. He was about to be late.

Done? Now pretend you’ve forgotten that and read this version:

VERSION TWO

He had two fingers shoved in the little pocket where he kept his watch, feeling the tick tock in his fingertips like the pulse in his veins.

It seemed like it was slowing.

His brown hat bowed as he squinted at the minute hand. How many ticks did he have left before the train came? How many tocks before he stepped aboard for the last time? How many heartbeats before he flinched at the hiss of the air brakes, anticipating the final exhalation of his own rattling lungs?

The endless city seemed to press down on him, a steel and glass jungle clogged with concrete and grime. But he stood frozen in the bustle, a static chocolate freckle in the surging confetti sea at the corner of 3rd and Main.

He could almost feel it scream closer, slipping beneath skyscrapers that rubbed shoulders with factories, squeezing past overflowing shops and cafes, shoving aside crowds that oozed through bottleneck alleys.

And then suddenly it was before him, light strobing off its speeding windows, the tracks screeching with sparks. Slower and slower until it stopped, staring at him.

The train was on time. He was about to be late.

–

Leave your verdict in the comments!

–

How to be Original

You’ve been working on your novel for several years when you discover the latest uber popular YA book is exactly like yours. And you curse the author’s earlier timing because if you ever manage to publish yours, everyone will say you copied hers.

Then you think about it and realize your book is a mix between Out of the Silent Planet, Lord of the Flies, Ender’s Game, and The Elfin Ship. It’s the mess of words you’d discover on your carpet if your home library threw up.

Crap.

So you throw the idea out the window and sit down to your notebook, determined to come up with something truly new. But after a few hours, all you can think of is a bunch of ideas that have been done several times. For instance:

- The chosen one

- Anyone with super powers

- Villain turns out to be hero’s father

- Genius child is amazing at everything

- Eccentric genius solves mysteries

- Orphans

- Forbidden love

- People who see the unseen

- Art and literature are outlawed

- Everyday life is a lie

- Last man on earth

And this is just a small sampling of the ideas that have passed from fresh to done to copied to trendy to cliché. The more you see of the world, art and literature, the more you’ll realize it is all the Same Old Thing. King Solomon said it best: ain’t nothing new under the sun.

He might’ve worded it differently.

Anyway, the point remains. There are no new story ideas. But that’s not such a bad thing. Some story arcs are timeless, so long as they’re driven by strong, interesting characters. Because, while of course we should take the plot road less traveled whenever possible, plot is not the key to being original.

Take it from my favorite writer:

No man who bothers about originality will ever be original: whereas if you simply try to tell the truth (without caring twopence how often it has been told before) you will, nine times out of ten, become original without ever having noticed it.

– C.S. Lewis

Tell the truth. Tell what you know. Whether you’re actually writing your memoirs or a Martian adventure story, deep down you’re still writing from your own experience. So find the words to most clearly and vividly state what it feels like to be you.

Succeed (it isn’t easy) and one of two things will happen: Either readers will say, with astonished wide eyes, that they never looked at it that way before. Or readers will say, breathless with excitement and tight-throated with tears, that they’d thought until this moment they were the only one who felt that way.

Either way, you have accomplished something incredible.

—

How Long Should a Scene in a Novel Be?

Goodness knows how many times I’ve advised you to cut the fluff in your novel. But there is such a thing as cutting too much. If your goal is “as short as possible!” you might end up cutting more than the fluff—important stuff like character development and symbolism.

So wouldn’t it be better to aim for a specific length—like a range of words? But what range should we aim for? What are successful authors doing?

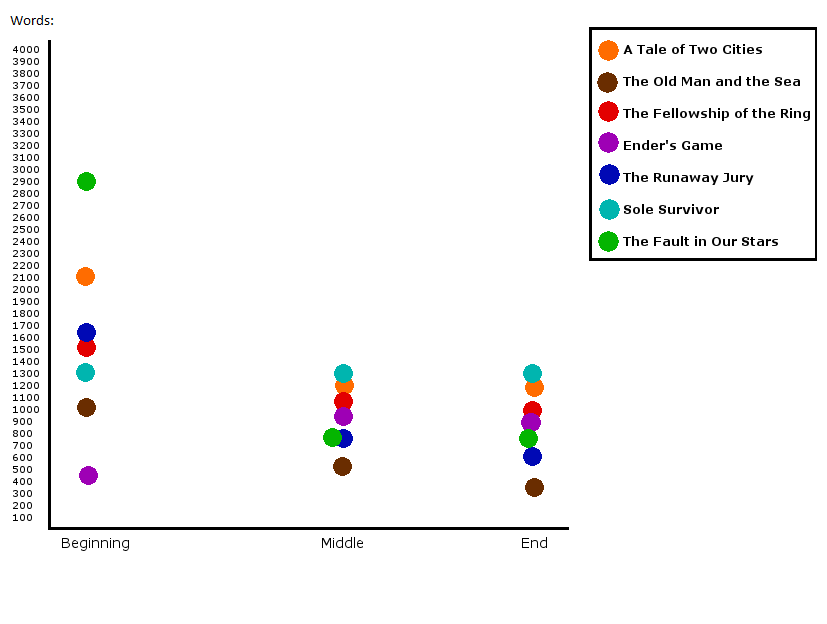

I decided to find out. I pulled seven novels off my shelves for my research. I tried to choose a good variety: the publishing dates ranged from 1859 to 2012, and genres included Literature, Suspense, Science Fiction and Fantasy.

This is NOT an exact science, people, so don’t take any of these findings as gospel truth. But I did find a few things that could be useful guidelines for us. Check out my lovely redneck graph showing (approximate) average words per scene for the beginning, middle and end of each book.:

The Takeaway

- All the books had a mix of longer and shorter scenes

- Longer scenes tended to appear toward the beginning, when the author was setting up character and setting

- Scenes were almost uniformly shorter (the action sped up) in the middle and end

- There were still occasional long scenes in the middles and ends of these books—usually scenes that introduced new characters or situations (more setup), or were action-packed climaxes

- One curious thing: though the number of words per page was different for each book, all the books seemed to have lots of scenes that were 2-4 pages long. This makes me wonder if publishers choose book sizes based on average scene length, to create the illusion of a certain pace. But I’m probably over-thinking it.

- We can be confident keeping most mid-to-end scenes between 300 and 1300 words. Earlier scenes can be longer.

Here are the detailed results and more than you ever wanted to know about how I got them:

What Counts as a Scene?

Scenes in novels are not always rigidly defined. I tried to measure scenes that were mostly action and/or dialogue, and avoided long chunks of exposition (which usually occur at the very beginning of novels, in the setup) and internal monologues (which are often used to transition from one scene into another). I didn’t feel these were proper “scenes,” as they occur inside the mind. Where action was tightly mixed with exposition (again, usually in opening scenes, especially the one in Runaway Jury), I counted it all. The hardest to measure were the middle scenes in Old Man and the Sea, which were an ambiguous mix of internal monologue and action.

Items that marked the beginning or end of a scene included:

- Chapter breaks

- The passage of time, indicated by:

- Formatting (*** or extra blank lines between paragraphs)

- Narration (“As the sun set,” “he awoke,” “two hours had passed,” etc.)

- Changes of setting

How I Measured

It might be more accurate to count every word in every scene in every book, but who has that kind of time? Instead, I looked at various scenes at the beginning, middle and end of each book, and multiplied the page numbers by the number of words on an average page (an average manuscript page is about 250 words, but paper and font sizes vary with published books, so I had to do sample page counts for each book—for instance, my copy of Old Man and the Sea has about 180 words per page, whereas my Fellowship of the Ring has over 500 words per page).

The Detailed Results

If I could confidently define one scene in the first few pages, I only measured that one (those that say “First ‘proper’ scene”). If heavy exposition or other factors made the opening scene less definite, I measured several scenes and counted a range (those that say “Opening Scenes”). Where you see a range followed by a parenthetical number, that means most scenes fell within the range, but I saw one that was the length in parenthesis. The marks you see on the graph are approximately mid-range.

A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens (1859, Literature) WORDS/PAGE: 300 FIRST “PROPER” SCENE: 7 pages | 2100 words MIDDLE SCENES: 2-6 pages | 600-1800 words CLOSING SCENES: 2-6 pages | 600-1800 words The Old Man and the Sea by Ernest Hemingway (1952, Literature) WORDS/PAGE: 184 FIRST “PROPER” SCENE: 5.5 pages | 990 words MIDDLE SCENES: 2-4 pages | 360-720 words CLOSING SCENES: 1-3 pages | 180-540 words The Fellowship of the Ring by JRR Tolkien (1954, Fantasy) WORDS/PAGE: 500 FIRST “PROPER” SCENE: 3 pages | 1500 words MIDDLE SCENES: .5-4 pages | 250-2000 words CLOSING SCENES: 1-3 pages | 500-1500 words Ender’s Game by Orson Scott Card (1977, YA Sci Fi) WORDS/PAGE: 300 OPENING SCENES: .5-2.2 (8+) pages | 150 – 660 words (2400) MIDDLE SCENES: 2-4 (6) pages | 600-1200 (1800) words CLOSING SCENES: 2-4 pages | 600-1200 words The Runaway Jury by John Grisham (1996, Suspense) WORDS/PAGE: 300 FIRST “PROPER” SCENE: 5.5 pages | 1650 MIDDLE SCENES: 2-3 pages | 600-900 words CLOSING SCENES: 2 pages | 600 words Sole Survivor by Dean Koontz (1997, Suspense) WORDS/PAGE: 380 OPENING SCENES: 2-4.5 (8) pages | 760-1710 (3040) words MIDDLE SCENES: 2-5 pages (8.3) | 760-1900 (3154) words CLOSING SCENES: 2-4 pages (10) | 760-1520 (3800) words The Fault in Our Stars by John Green (2012, YA Literature) WORDS/PAGE: 250 OPENING SCENE(S): 10.33-13.33 pages | 2582-3332 words MIDDLE SCENES: 2-4 pages | 500-1000 words CLOSING SCENES: 2-4 pages | 500-1000 words