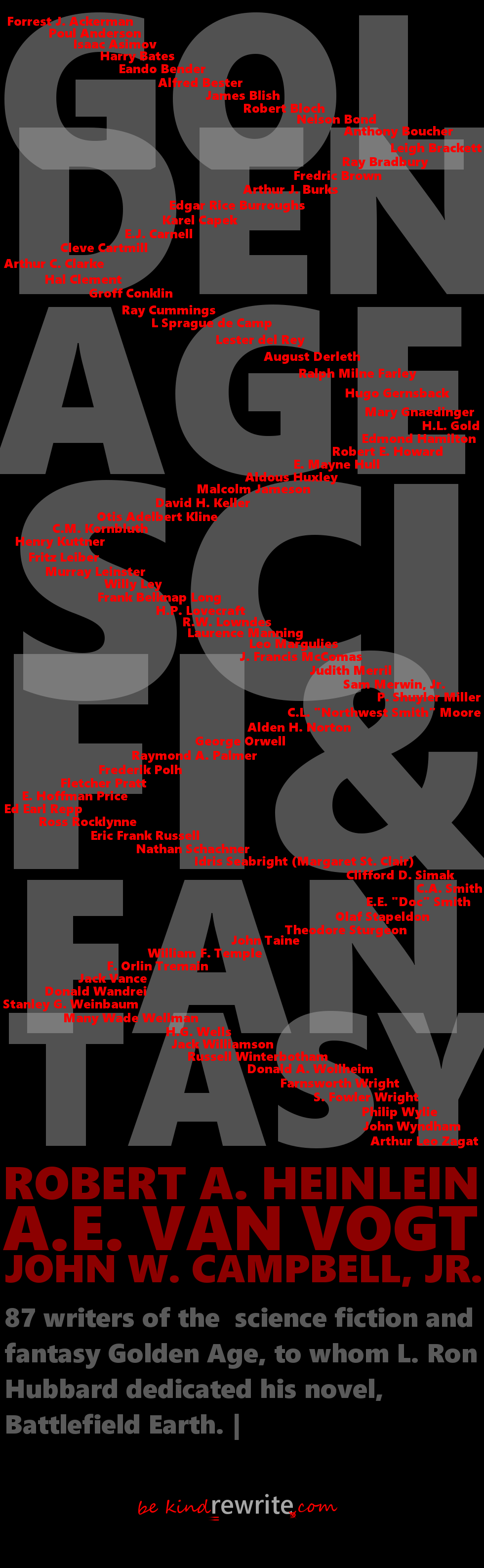

Well, I promised you a sci-fi short, and here it is. It ended up being too long for flash fiction, though, so I’m posting it in five parts.

I’m not sure how I feel about it.

—

Part I

Image by Chris Samuel

The most powerful telescope in the world was a relic. Once man’s only window to the further reaches of the universe, now a third-rate museum presided over by a pile of rickety joints who had never completed his Ph.D., and the boy he had hired for the summer.

Sometimes in the fall and winter, the train would bring a wash of sixth graders from the local middle school to liven up the place for an hour or two. The rickety joints would lean on the stair rail at the telescope’s sight, rasping the history of the space program over a chorus of whispers, giggles, and bored sighs.

“But eighteen days after its completion,” he said, “Harmon Graham successfully tested the first Spacial Disruption engine. And that,” the rickety joints paused, staring at nothing for several seconds, until some of the children began to snicker. “…Was that,” finished the old man at last.

It wasn’t that modern schoolchildren had lost their longing for the stars; most thought themselves destined to be explorers in the S.D. fleet. But they hardly found it interesting to look through a device at the boring old moon (all that could be seen in the middle of the school day), when on the webs they could find hi-res photos and video of truly distant planets, taken by astronauts who were actually there.

The boy was different. The other kids could try their luck with the S.D. program when they were old enough—he couldn’t. Even the ones who failed the rigorous flight school could save up their pennies and visit the safaris on Kepler-62f. But he could never leave the skin of the Earth.

Of course, there were a lot of things he couldn’t do. By law, he couldn’t be a surgeon. He could never have children. His parents had to apply for special dispensation just to give birth to him.

But the stars were closed to him by more than the law of man. The miracle of technology that gave mankind access to even the most distant worlds in the blink of an eye—that technology would fire in his brain like the seizures that sometimes plagued him. But stronger: strong enough to kill him.

Yet it was the stars he longed for most.

Have you ever craved something you were deathly allergic to? That was the boy and space travel. He sometimes prayed and asked God why he had this longing he could never satisfy. Sometimes he searched the webs for some scientific rationale. But God gave him no answer, and science was indifferent.

When it was his class’s turn to visit the old observatory, and he had stared through the great glass lenses at that daytime moon, he knew this telescope was the closest he would ever get. And that summer, he begged the rickety joints for a job. The old man had frowned at him, his deep wrinkles nearly hiding his eyes.

“No.” He was firm. “Nothing for you to do. Why’d you want to work here, anyhow?”

“Why’d you?” shot back the boy.

“’Cause the past is important,” snapped the rickety joints. “You can’t hold on to what you have if you don’t know how you got it.”

“Teach me,” said the boy. And the old man sighed, flicked his hand dismissively and limped over to the supply closet. He drew out a broom and shook it at the boy until the boy came and took it from him.

“Two rules, kid. One, if you open your mouth, it better be to ask a question. You’re here to learn, not to yammer in my ears about what you already know. Two, no looking through the scope when I’m not here.”

The boy opened his mouth, then closed it and nodded.

“Well get going then.”

So the boy came every night and swept the floor that didn’t need sweeping. Once each night the man tottered in and sat in the chair in the corner, and told the boy how to angle the telescope to see Asimov-5a, or Lutwidge-7. And the boy could look through and see craters and canyons and seas. Soon, the old man taught him the use of the more powerful lens, and he could pick out pebbles in a dried river bed. Hundreds of light-years away, and it was like he could reach out and touch it.

There were maybe a dozen different stars and planets that they looked at over and over. Eventually, the rickety joints would say “aim at Kepler-3b,” and the boy would have to do it from memory.

One night, the boy diverted from the old man’s instructions. He twisted the knob to aim the scope just slightly higher. “Why don’t we look at Campbell-38 tonight? We always look at Kepler-3b, but never Campbell-38.”

The rickety joints shot out of his chair and bellowed. “No! Away from there!” he grabbed the broom and rapped at the boy’s ankles. “You look at no worlds but those I’ve taught you.”

The boy rubbed his ankle. “But why?”

“Because I say. If you want to see Campbell-38, you can find pictures on the webs. Not through my scope.”

So when the boy went home in the wee hours of the morning, he searched the webs for photos of Campbell-38. There had only been one expedition there, but there were plenty of photos. And there were mountains and canyons and strange rock formations. Much the same sights he had seen on the other worlds.

But photos were photos. They could be made to look like anything. What you spied through a lens was the real thing.

The boy knew this.

And he wondered what the old man—and what the entire S.D. program—was trying to hide.

The old man spent more time in the observatory for several nights after that, keeping one eye on the boy as he read his books. But the boy did everything he asked and nothing he didn’t and so the old man eventually left him alone again, to sweep the floor that didn’t need to be swept.

That was when the boy made his move.

—

Tune in tomorrow for Part II!

–