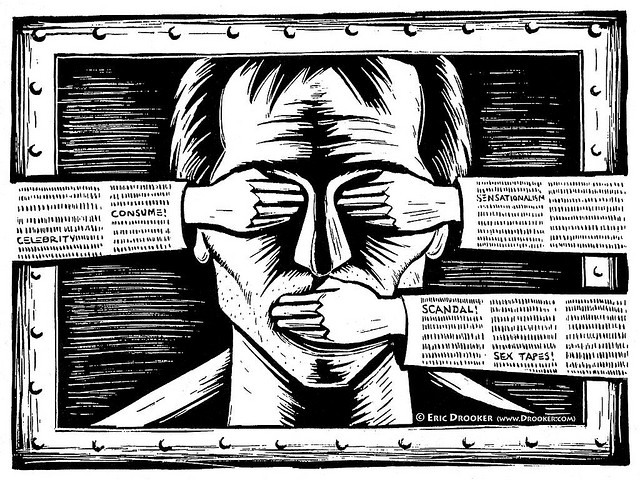

Next week is Banned Books Week, when we stand up for the right to read whatever we darn well please! It’s when organizations like the National Coalition Against Censorship lead us in “promoting freedom of thought, inquiry and expression and opposing censorship in all its forms.”

In all its forms? Is censorship always that black and white?

I don’t think so. Here’s why.

1. There’s a difference between school censorship and country-wide censorship.

Country-wide censorship, in which a government controls what its adult citizens read, is tyranny. It is always wrong. If you’re 18 or older, you should be allowed to read whatever you want.

But censorship for children, as in banning books from a school curriculum, is different. Children of certain ages shouldn’t be exposed to certain content; most of us would balk at the idea of a ten-year-old reading Fifty Shades of Gray. It’s the parents’ prerogative to decide which content is appropriate for their children, at which ages.

2. There’s a difference between censoring ideas and censoring inappropriate content.

As we all learned in the movie Inception, there’s nothing more powerful than an idea. And literature (or media as a whole) is the channel through which ideas are transported. Control which ideas your people hear and you control your people.

That’s why country-wide censorship is wrong: without freedom of thought, there is no freedom, period.

The idea is the thing that must not be censored. And there are many ways to express an idea – ways to do it without being crass. For instance:

“The government is f—-d up” vs. “The government is useless/messed up/wrong.”

They express the same idea – an idea that threatens authority. The expletive might be more fun to say, but it’s unnecessary.

Now, per #1 above and #4 below, no government has the right to outlaw crass content. But if an author is angry his book was banned from a school curriculum for including a few F-bombs, my advice to him would be to stop using F-bombs.

Of course, it’s more complicated than that:

3. It’s difficult to determine how inappropriate something is.

The F-word has made its way into PG-13 movies, yet The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn has been banned for the N-word. Why is the N-word so much worse? It’s a racial slur, an insult to a particular group of people. But then why isn’t the B-word just as bad, when it insults an entire gender?

4. Sometimes it might be necessary to use inappropriate content to express an important idea.

I suppose the idea is to ban the N-word from our language altogether so that children won’t learn to use it. On the other hand, isn’t it an important part of human history that should never be forgotten, lest it be repeated?

5. It’s difficult to determine what is actually inappropriate and what simply conflicts with the beliefs of one group of people.

The Atheist parent might not want their child saying “under God” in the American pledge of allegiance at school.

The Christian parent may not want their child reading Heather Has Two Mommies.

Yet the Atheist parent would likely fight to keep Heather Has Two Mommies, and the Christian would likely fight to keep “under God.”

So where does censorship draw the line?

Does it ban anything that might offend? The kids won’t get to read anything at all. Does it allow everything? That infringes on the rights of parents who can’t afford to send their kids to a different school if they disagree with the curriculum.

There has to be some middle ground.

In the video below, John Green describes a decent solution – parents sign permission slips for their kids to be taught books that might contain objectionable content. But he also mentions some parents who weren’t satisfied with the solution:

(Here’s the link in case the embed doesn’t work.)

Censorship of the content your child consumes is your right. But censoring the content other parents’ children consume, against those parents’ wishes, is wading into tyrannous waters. If we allow that to happen in our schools, it will soon make its way into our homes.

So is censorship simple? No. Is it always wrong? No. But is a dangerous form of censorship still a threat to the free world?

Absolutely.

—