Erin asks: I was recently watching a movie (The Huntsman Winter’s War) with my sister. My sister and I didn’t enjoy it for multiple reasons. One of them was that fact that the whole plot is filled with side stories because one was not enough to make a full movie (though each story could have been much longer with more creativity). So basically, we were jumping from story to story. I started to wonder if I am doing that unintentionally. I have one main story, but I have different, smaller conflicts too to go along with it. Is this too much? How do you tell if you’re patching little stories together and don’t have one main focus? How do you ‘cure’ this?

—

I don’t feel wholly qualified to answer this, since I haven’t given the subject much thought until now, but the question intrigues me. I tend to love subplots, but I also recently watched a movie with a terrible subplot that totally bored me. My response any time this subplot reared its head was “Why are you showing me this?” It had zero bearing on the main story.

The truth is, any given story contains infinite other stories. Each secondary character is the hero of his own story, with its own secondary characters who each have their own stories and so on and so forth. We can’t tell them all. How do we decide which ones to tell?

Whichever stories serve the main plot.

The main plot, the one that follows your protagonist, is the one your readers are (hopefully) invested in. Any subplot that doesn’t directly impact the main plot by the end, doesn’t belong in the story. Subplots generally impact the main plot in one or all of these ways:

- Helps the hero

- Hinders the hero

- Provides important information about the hero’s background or enemy

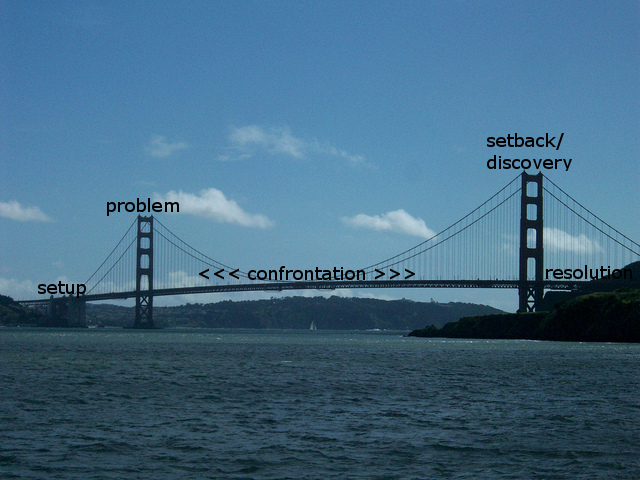

Structurally, there are a few different ways to use subplots.

Subplot Structure 1: Split and Converge

Lord of the Rings is a great example of subplot use, and one you’ve probably read or seen, so I can probably go into more detail without spoiling it for you.

The main plot is the mission to destroy the Ring. Nine characters undertake this mission at first, but are soon broken up, and then only Frodo and Sam are carrying the Ring. Why do we continue to follow Merry and Pippin, the three warriors, and Gandalf?

First, because we’ve come to care about them. Just as the members of the Fellowship have grown close to each other, we have grown close to them. Aragorn’s pledge not to abandon Merry and Pippin to death by Uruks despite their broken Fellowship is also Tolkein’s pledge not to abandon their stories. The Fellowship holds for the readers as well as the characters.

Secondly, their further travels teach us things about Middle Earth that are relevant to Frodo, Sam and the fate of the Ring. Frodo and Sam’s journey is relatively isolated—so much so that Frodo himself begins to forget what they are fighting for. It’s the rest of the broken Fellowship that reminds us of the good in the world (as we see the Ents, Rohan, and Gondor) and simultaneously shows us what peril that world is in (forests burning, armies of Orcs and Urukai’, a possessed king of Rohan, and an insane steward of Gondor).

In this way, the subplots actually make us more invested in the main plot. They give it scope and resonance. Here are kings and armies fighting and dying in the name of a trinket held by a couple of humble Halflings. If all we saw was the trinket and the Halflings, we wouldn’t care nearly as much.

Thirdly, they are still all invested in the main plot. What happens to the Ring affects them. In fact, all our original friends (and some we met along the way) end up at the Black Gate of Mordor at the end, to draw the orc armies away from Mount Doom, so Frodo and Sam can finally destroy the Ring. Directly affecting the main plot again. It all comes full circle.

Subplot Structure 2: Surprise Convergence

Both Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities and Sachar’s Holes break away from their main plot to tell us other stories; stories that don’t seem to have more than a tenuous connection with the main characters. Yet by the end, everything comes together; the side stories turn out to be the keys to the mysteries presented in the main story.

This subplot method is riskier, because your readers must have patience, and trust you to reveal the relevant connection in the end, but it can also make for a very satisfying “aha!” resolution. It’s especially useful if you need a lot of backstory to explain what’s going on—instead of telling all the backstory before getting to the main story, you tell both at the same time, jumping back and forth.

Subplot Structure 3: Themed Connection

The movie Love Actually is more like a collection of interwoven short stories. There is no main story, but it does have a theme (romance), and all the individual stories are variations on that theme (love lost, won, unrequited, etc.). The stories do sort of all come together in the end, but only incidentally (the characters all know each other and happen to be going to the same place), not in a plot-relevant way (the stories don’t really affect each other).

If the stories didn’t vary, or conversely if they varied too much and didn’t even share a theme, the movie wouldn’t work. As it is, the individual stories may be shallow (some more than others), but breadth, not depth, is the aim.

A fourth subplot structure may be the use of a single subplot as comedic relief. This only works if it brings something new to the story and genuinely lightens up something that’s pretty dark. The movie that annoyed me the other day was basically a rom com/dramedy, and they added a rom com subplot. The movie was already funny—it didn’t need comic relief, and it certainly didn’t need more shallow romance.

Anyway, I hope this helps. In case it doesn’t, here’s a ninja lamenting the many plotlines in the second Pirates of the Caribbean movie: