Does your story sag in the middle? Do you feel like you’re plowing through boring scenes just to get to the cool ones? Is your protagonist wandering around aimlessly, looking for the climax?

It’s not enough to have all the major events written down in a neat little list – what you need is structure.

An important distinction

Structure is not formula:

- Formula is like having the same floorplan over and over.

- Structure is a floor, walls and roof: you can organize them into whatever floorplan you like – but you can’t build a house without them.

Structure is the ebb and flow of tension and discovery that keeps you readers moving through the story. Structure helps you:

- Keep the pace up

- Know what’s important and what isn’t

- Understand when to start and end the story

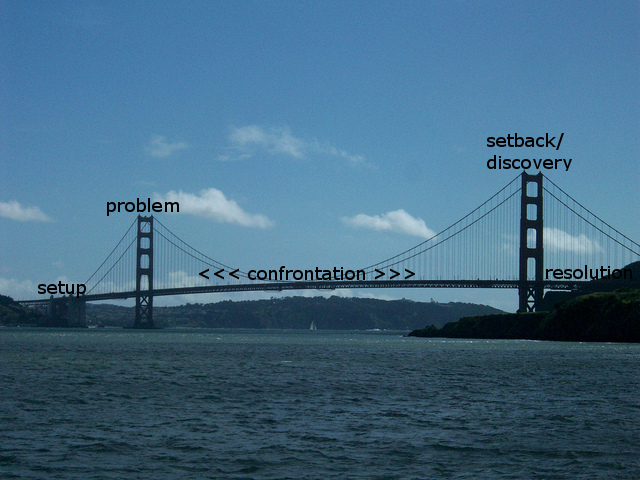

The following is a time-honored plot structure endorsed by Syd Field and others.

Structure of a Plot

Setup

In Act I, or the beginning of your story, you introduce the hero. We learn what he cares about and decide if we like him. This part should be relatively short. Keep the backstory to a minimum: it’s only an introduction.

Examples:

- Bilbo celebrates his eleventy-first birthday

- Luke buys some used droids

- Passepartout starts a new job under Fogg

Problem

Within the first or second chapters, introduce the problem. Syd Field calls this Plot Point 1, which hooks the action and spins it into the next act. James Scott Bell calls it the first “pillar” of your plot “bridge,” or the first Door of No Return. This usually happens in a single scene – maybe at the end of the same scene you used to introduce the character.

Examples:

- Frodo learns an evil something is coming to the Shire in search of Bilbo’s old Ring.

- Luke’s aunt and uncle are killed, and he’s got the droids their killers are looking for.

- Passepartout’s new boss bets some friends he can circumnavigate the globe in 80 days. Starting tonight.

Confrontation

Now we’re in the middle, or Act II of your story. This is the biggest chunk of the book. Your hero will face a series of obstacles, each more difficult than the last. As he overcomes each obstacle, the plot thickens, the tension increases, and the stakes are raised. In other words, new developments reveal that the hero stands to lose (or gain) even more than he originally thought.

Your hero should be getting more and more desperate; the pace should get quicker and quicker.

Examples:

- Frodo and his friends face wraiths, orcs, trolls, giant spiders, etc.

- Luke saves a princess, escapes the Death Star, loses his mentor, etc.

- Passepartout and co. fight through bad weather, savage attacks, etc.

Setback/Discovery

Plot Point 2, the second pillar of the bridge, or the second Door of No Return. This is the worst setback and/or the major discovery that signals the climax. Your hero is now either armed with new information that leads him to a final showdown with the villain, or has been brought to his lowest point – he is betrayed, or he’s been shot, or the girl he’s been trying to save all this time gets killed, etc. The villain believes he has won.

It’s at this point the hero must make a decision. The ultimate decision.

Examples:

- Setback: an army of orcs between Frodo and MountDoom. They disguise themselves as orcs. Decision: Frodo decides whether to keep or destroy the Ring.

- Setback: Luke, now a rookie rebel fighter, is the last armed fighter left against the giant space station. Decision: Whether to trust the computer or the Force.

- Setback: After being detained, Fogg and co. believe the game is lost. Decision: Fogg decides to marry the girl he loves.

Resolution

The End, or Act III. The climax and conclusion are the results of his ultimate decision. Does he win or lose, learn a lesson, live to fight another day?

Examples:

- We find out who survived, who married whom, and who leaves Middle Earth.

- We find out if Luke succeeds or fails and what that means for the Rebel Alliance.

- Passepartout sets out to find a priest to do the marrying, when he discovers they arrived in town a day early – and we find out if they make it in time.

So there you have it. Just follow the bridge to get safely across to happily ever after.

—

My problem with sagging plot is usually in between the two pillars – the longer the piece of writing, the more has to go in here, and most structure plans like this are pretty vague on that area (“increasing tension”, “increasingly difficult obstacles” etc). I understand why, as it’s so story-specific, but I’d love it if you had any tips for that section in particular!

It’s definitely where I have trouble, too. It might help to think of the middle as a series of smaller conflicts and resolutions all leading up to the Big One. More importantly, here’s a post I wrote awhile back with a big collection of tips from other writers about increasing tension.

It seems to me that this can be applied on a mini-scale for each chapter. If there isn’t a major event (for the protagonist) in the story, then they’re not advancing/developing. I like that you pointed out the main character getting more desperate. It helps me feel the mood. Thanks for the past!

Yes; good point! Elizabeth Sims advised structuring your story around all the “heart clutching moments” that occur. Something important and hopefully exciting should be happening in every scene.

I appreciate how the hero myth story structure works and you’ve laid it out nicely here, but now I’m faced with the same question that Charlie Kaufman faced in ‘Adaptation’.

Does every story have to follow this structure in order to be interesting?

I’m afraid I haven’t seen Adaptation, so I’m not certain I know what you’re asking, but I’m going to say “yes.” You should follow the basic structure. But that doesn’t mean you have to follow all the examples I gave in the post. It doesn’t have to be a physical battle with a definite villain. There doesn’t have to be action or romance. It could be an emotional battle. The hero could be his own antagonist. But you need a beginning, middle and end just like you need a first page, a last page, and pages in between. But maybe you start in the middle, jump back to the beginning and then finish up with the end. In whatever order, the important part is that you have all three. And you need conflict and resolution – they are the essence of story. Somebody has to want something, and they have to succeed or fail at getting it.

So don’t get caught up in the specifics of this post – just the basics. Chances are, your story already fits this structure, at least loosely. It’s knowing the structure that helps us see the big picture of our book, where we need to cut scenes or add scenes to keep the story moving.

Does that help?

I think I may have fixed an early pacing problem in a way that helps the plot! Here is hoping, anyway. Pacing is something I always second-guess… and third-guess etc…

Yay for that!

There does come a point when pacing is just relative. A lot can depend on the reader’s state of mind – if they are distracted while reading a pivotal scene, pacing might seem too quick because they are having trouble absorbing it all. Or if they’re feeling antsy while reading a scene that doesn’t appear to be important, it will seem too slow. On our part, we have to just do what we can (like with plot structure, not letting scenes get too long, alternating fast and slow scenes, etc.), and rely mostly on beta readers to tell us whether or not we’ve succeeded.

In past drafts, I had this curious habit of just retelling/summarizing important scenes with character dialogue later, instead of actually writing the scenes. Still smacking my forehead over that one.

“In past drafts, I had this curious habit of just retelling/summarizing important scenes with character dialogue later, instead of actually writing the scenes. Still smacking my forehead over that one.” My instincts run towards doing this, too, and I am trying to fight it. I don’t know if I am just afraid of messing up the scenes themselves or if I really do consider characters’ reflections on them more interesting, but… yeah.

Ah yes, perhaps that’s why – being more interested in character’s reflections on events, I mean. We want to hear it in their words instead of our own?

Part of my problem was order of events…the order in which the main character met the others forced me to summarize a lot. I simply (simply???) had to move all that around. I think it was also partly because I was trying to rush through the beginning stuff to get to the really fun climax stuff, not realizing I was missing opportunities for other fun stuff. Brain playing tricks on me, I suppose.

Very likely… their own words and with the impact it had on them. That’s why my wee vampire refused to cooperate with my writing any of his story until I let him tell it. Speaking of which, he insisted on being involved in Voice Week. I am willing to bet you will figure out which one he is even without knowing much about him. What do you say. Willing to try?

Maybe. It is probably better re-ordered and un-summarized, but I am also convinced that writers who really think about their craft are usually too hard on themselves. It might not have been as bad as you think. 😉

Challenge accepted. I will find your vampire!

I acknowledge being too hard on myself, but it really was that bad. Fortunately, it’s getting better!

Yay!

Getting better is all any of us can strive for, really.